xMemory: Why Top-k Retrieval Breaks for Agent Memory

Introduction

LLM agents no longer begin and end in a single context window. We’re now in the era of cross-session, long-running agents. Products like Claude Code, OpenClaw, and other agentic workflows are built to carry context across days of work, not minutes. The bottleneck is not context length anymore. It is memory retrieval: deciding what to pull from a growing history under a strict token budget, without dropping the one earlier turn that makes a later instruction interpretable.

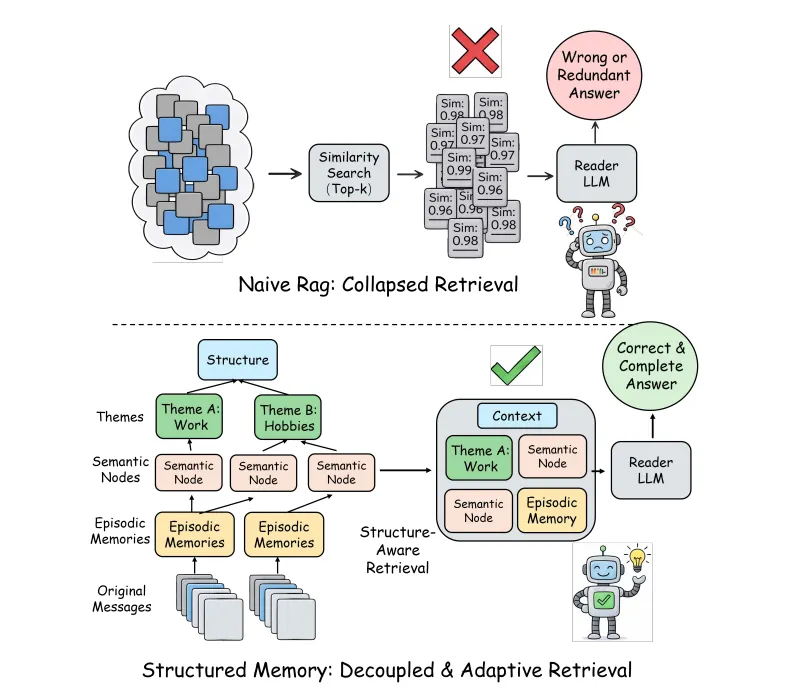

Most production systems still default to RAG. They embed past chat chunks, retrieve a top-k by similarity, and paste them back in. Hu et al. (2026) argue agent memory is a different distribution. It is redundant, tightly linked across time, and full of small updates that override earlier statements. Similarity search often collapses into near-duplicates, and pruning tends to remove the “glue” that keeps the timeline coherent.

At the same time, the industry is also moving toward a different retrieval pattern that clearly works in practice, especially for code: tool-driven lexical search. Think “grep the repo, follow the paths, open the right files.” This is valid and often the best default for codebases, but it does not solve conversation memory. You still need a way to avoid duplicate recall, preserve dependencies across time, and retrieve the minimum set of facts that makes later turns interpretable.That is the gap xMemory is trying to fill. It changes the unit of retrieval by decoupling conversations into semantic components, aggregating them into a hierarchy, and retrieving top-down for coverage without redundancy.

The problem: agent memory isn’t a document corpus

Classic RAG was designed for large, heterogeneous corpora. Manuals, web pages, PDFs, and internal docs are loosely related. Similarity search works well in that setting because relevant information is usually spread out.

Dialogue memory looks nothing like that. A user’s conversation history is highly correlated. The same topics appear repeatedly. Preferences get restated. Plans get refined. Constraints get updated. Most turns are variations of earlier ones.

In this setting, similarity search develops a predictable failure mode. Instead of finding diverse supporting evidence, top-k collapses into a single dense region of the embedding space. You get five versions of the same idea. Meanwhile, related information that sits slightly farther away never gets retrieved.

For agent workloads, that is disastrous. Many queries are inherently multi-factor:

- “What did we decide about timeline and budget?”

- “Why did we reject option B?”

- “What are my current preferences for this project?”

Each of these requires pulling information from different parts of the timeline. Top-k is structurally bad at that.

Why pruning does not fix it

Once redundancy shows up, teams usually try to compress. Retrieve top-k. Summarize. Prune. Hope for the best.

The paper argues this is especially risky for conversations. Meaning in dialogue is often spread across turns. Pronouns, references, corrections, and implicit assumptions tie messages together. Remove the wrong sentence and everything downstream becomes ambiguous.

You do not just lose tokens. You lose interpretability. This leads to a subtle but important reframing:

RAG is about finding relevant passages.

Agent memory is about reconstructing a coherent timeline.

xMemory’s core idea: decouple, then aggregate

The way I read xMemory is this: most memory systems fail because they never stop treating chat history as “a pile of messages.” Everything else, embeddings, pruning, reranking, is just damage control on top of that.

Once you accept that raw chat turns are a bad retrieval unit, a lot of the design suddenly makes sense. xMemory’s main move is to restructure memory before it ever becomes searchable. Instead of embedding thousands of loosely related turns and hoping similarity search figures it out, it tries to extract stable “components” first and organize them.

Conceptually, I agree with this. If you have ever looked at a long agent trace and thought “half of this is the same preference restated,” then you already know why chunk-based memory breaks.

But this is also where implementation gets hard. You are no longer just storing vectors. You are maintaining a living data structure that needs continuous updates, reassignment, and cleanup. That is a big jump in system complexity, and it is easy to underestimate.

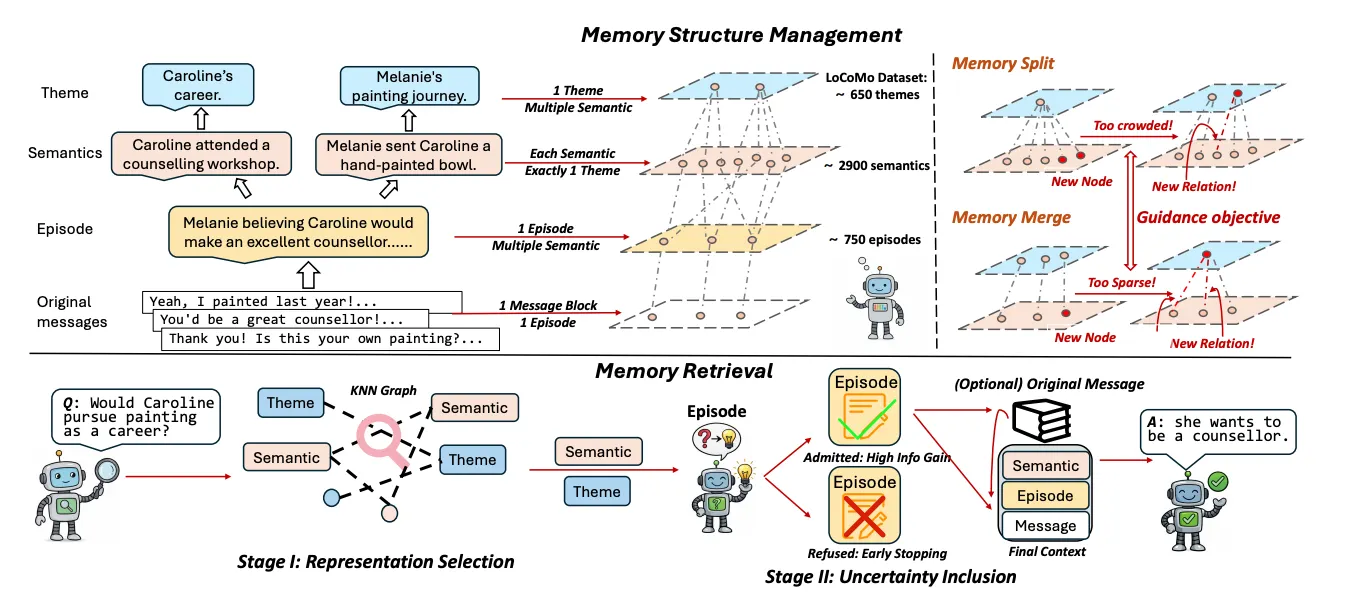

Memory is organized into four layers:

- Messages: the original raw dialogue turns, preserved verbatim as ground truth but rarely retrieved directly.

- Episodes: contiguous segments of conversation summarized into coherent blocks. Think "the conversation where we finalized the API design" rather than 40 individual messages.

- Semantics: distilled facts such as preferences, decisions, and constraints. If a user states the same preference three times across different conversations, it becomes one evolving semantic node - not three competing chunks.

- Themes: high-level groupings of related semantics that reorganize dynamically as memory grows. Unlike static embedding clusters, themes restructure based on how semantics actually get retrieved together.

This hierarchy allows the system to reason about memory at different levels of abstraction. Redundancy is handled early. Dependencies are preserved through links to episodes and messages, so retrieval no longer has to reconstruct structure that was never encoded.

To keep this hierarchy usable, xMemory continuously restructures it. Large themes are split, overlapping ones are merged, and misplaced semantics are reassigned. This plasticity prevents memory from fossilizing as user behavior changes.

How xMemory retrieves information

With structured memory in place, retrieval becomes a guided search rather than a flat ranking problem. xMemory proceeds from coarse to fine.

First, it performs representative selection at the theme and semantic levels. Rather than ranking by similarity and taking the top-k, the system selects components that maximize coverage of the query's requirements while minimizing overlap between selected items. If a query touches on both "timeline" and "budget," the system pulls one representative semantic for each rather than five variations of whichever scored highest.

Then, the system decides whether to expand into episodes and raw messages. Expansion is triggered when the reader model signals low confidence - if the retrieved semantics are too abstract to answer precisely, or if the query requires specific chronology or exact wording, the system drills down to finer-grained layers. If high-level semantics are sufficient, retrieval stops early. This creates a principled stopping rule that avoids both under- and over-retrieval.

Experiments: what changes in practice

The authors evaluate xMemory on LoCoMo and PerLTQA, two benchmarks designed for long-horizon agent memory. These tasks test whether a system can answer questions that depend on decisions, preferences, and constraints spread across long conversation histories.

The gains are substantial and consistent across model backbones. With Qwen3-8B on LoCoMo, xMemory improves average BLEU from 28.51 to 34.48 (+21%) and F1 from 40.45 to 43.98 (+8.7%). The improvements are especially pronounced on temporal reasoning - the category most dependent on preserving cross-turn dependencies - where BLEU jumps from 23.60 to 29.58 and F1 from 33.74 to 37.46.

With GPT-5 nano, xMemory reaches F1 of 50.00 and BLEU of 38.71, while simultaneously reducing token usage from 9,155 to 6,581 per query - a 28% reduction. The efficiency gains are even more dramatic when compared to structured memory baselines: against A-Mem, xMemory cuts tokens from 9,103 to 4,711 (48% reduction) while achieving higher accuracy. This is the core claim in action: structured retrieval surfaces denser, more relevant context without the redundancy penalty.

On PerLTQA, the pattern holds. With GPT-5 nano, xMemory improves F1 to 46.23 and ROUGE-L to 41.25, outperforming Nemori's F1 of 41.79 and ROUGE-L of 38.43. These results suggest the retrieval principles transfer beyond dialogue recall to broader personal memory reasoning.

Ablation studies show that structure management is critical. When split and merge operations are disabled, performance drops and retrieval becomes noisier over time. Without continuous reorganization, memory slowly degrades.

Perhaps most importantly, xMemory remains stable as histories grow. While baseline systems tend to deteriorate as redundancy accumulates, xMemory degrades more slowly because it actively reshapes memory. For long-running agents, that stability matters more than short-term gains.

When xMemory is overkill

xMemory solves a real problem, but that problem only emerges at scale. Before adopting it, consider whether your use case actually needs it.

Short histories don't benefit. If conversations rarely exceed a few dozen turns, redundancy collapse may not exist yet. Standard RAG with reasonable chunking will perform fine.

Diverse corpora still favor classic RAG. xMemory targets bounded, coherent dialogue streams. If you're retrieving from heterogeneous documents - manuals, knowledge bases, web pages - the original RAG assumptions hold and similarity search works well.

Latency matters. Top-down retrieval through multiple hierarchy levels adds inference steps. For real-time applications, profile carefully before committing.

Structured approaches are fragile. The paper notes that systems with strict schema constraints can cascade formatting errors into failed updates. Any hierarchy introduces this risk. If your LLM occasionally produces malformed outputs, simpler unstructured approaches may be more robust.

If you're not seeing retrieval collapse yet, you probably don't need the complexity.

Conclusion

Similarity top-k is a strong default for documents. It is a weak default for memory. Conversation histories are correlated, repetitive, and full of dependencies that top-k collapses and pruning breaks.

xMemory shows that fixing this requires changing representation, not tuning retrieval. By decoupling conversations into semantic components, organizing them into themes, and retrieving top-down, it becomes possible to build memory systems that are compact, diverse, and stable over time.

But the deeper lesson is that agent memory is a distinct retrieval problem. The field spent years optimizing RAG for document corpora - those techniques don't transfer cleanly. If you're building long-running agents, the question isn't whether to adopt xMemory's exact architecture. It's whether your system treats memory as "search over past messages" or as "reconstruction of a coherent timeline." Get the framing right, and the architecture follows.

for a deeper dive into the paper - Beyond RAG for Agent Memory